In grad school, late at night over drinks, my friends and I gave name to the “Disneyland Effect.” It refers to a kind of willed openness, a receptivity to experience and determination to enjoy that can occur when one has paid an ungodly amount of money for the experience itself.

We didn’t come up with the idea, of course – it’s the actual product you purchase when you buy a ticket to Disneyland, and it’s what inclines folks to tolerate the long lines, overpriced food and commercialized mayhem: I will be enchanted! And in these circumstances, it can lead to all manner of nefariousness and exploitation, that human urge for a smattering of wonder.

But it can be cultivated, too, this hunger to become dazzled. And travel is the easiest way to cultivate it. You’ve bought your ticket, paid for your hotel room, and there you are: somewhere new. You go out, wandering the streets of a place new to you, and you’re looking for things.

Even if you’re following an itinerary, some pocket guidebook: you wind up at that museum or view, and then you search (probably with that anxious voice needling you in the back of your consciousness: what am I supposed to be finding here?). Better, then, to wander, and keep the object of your search open-ended. And when you search, you will find: not always the thing you were looking for (thankfully), but sometimes something altogether better.

In Krakow, for instance, unsought for, I found this:

A gleaming mosaic on the exterior caught my attention, magpie-like, and drew me in:

Where my kind of vulgar, if ever-ravenous appetite for color was momentarily sated:

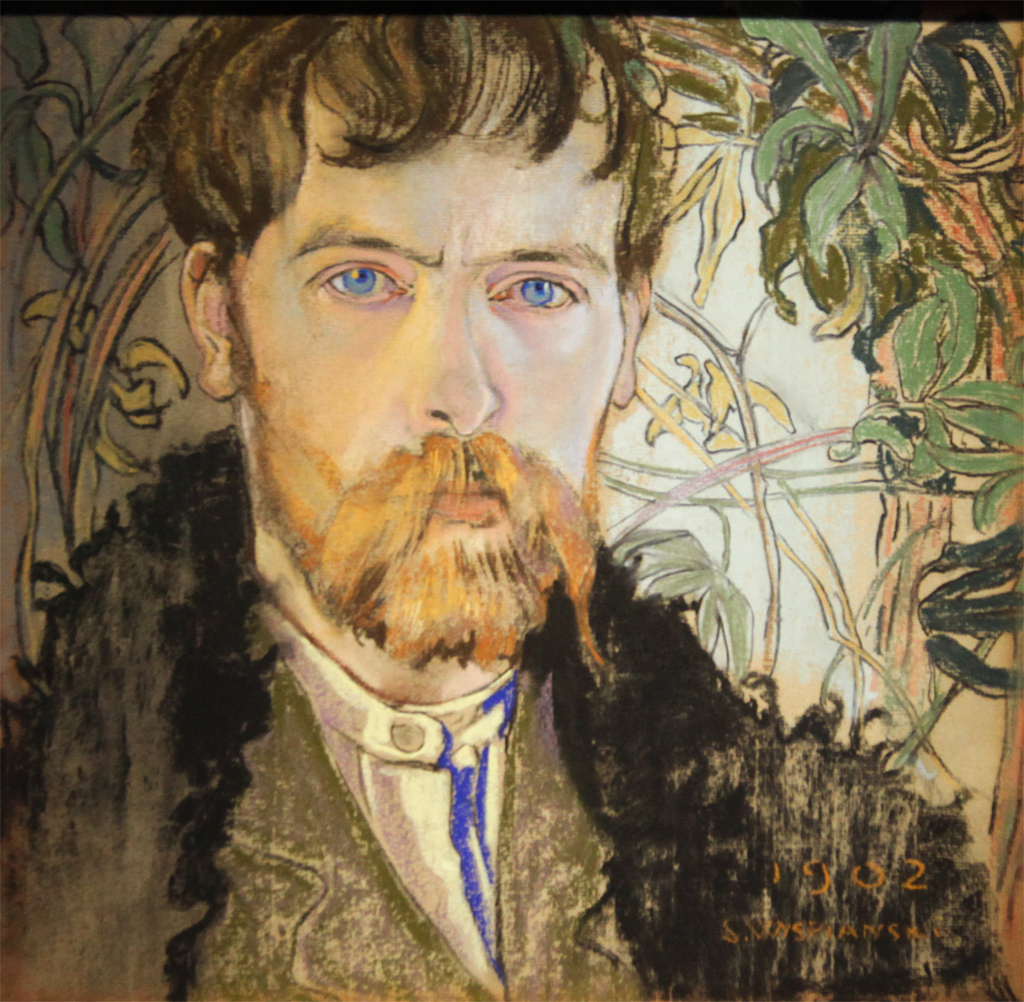

These wonderful stained glass windows struck a note of familiarity in me, though I’d never heard of the artist (whom a guidebook explained was one Stanislaw Wyspianski).

The sinuous lines and abstracted drama reminded me of Yeats, or one of those symbolist paintings that lay gleaming on the pages of a magnificent old art book that’s haunted the bookshelves of every place I’ve lived for the last 30 years or so.

Wyspianski, I learned, was a part of the Young Poland movement at the end of the last century, a contemporary of Yeats, in fact, though not as long lived. Like Yeats, he was a polymath – a poet and dramatist, a designer of interiors in the tradition of William Morris. And like Yeats, he was a romantic nationalist, someone who sought to create a soul for an as-yet unrealized nation from old myths and personal vision.

I’m fascinated by (and more than a little jealous of, I confess) the notion that for these poets, art was not only about self expression; It was also a deliberate effort to articulate, to actually create, the soul of a nation.

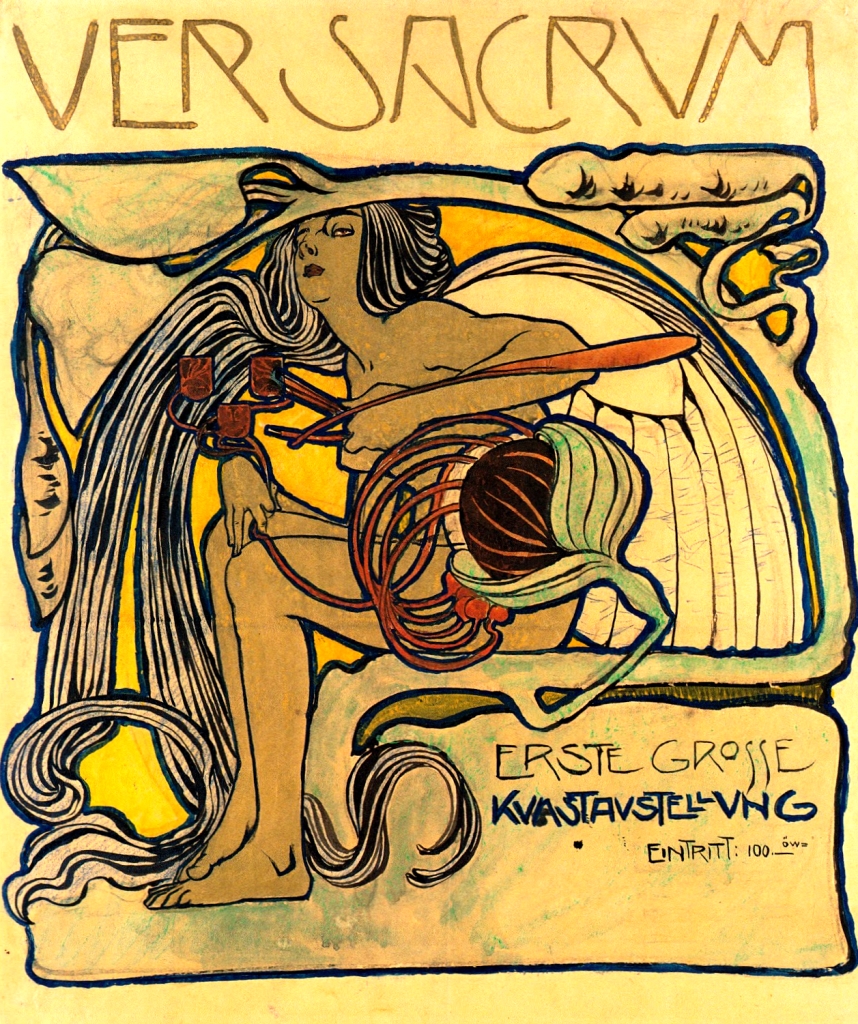

Design is a crucial part of this effort: space shapes the things it contains, whether in the cover of a book:

Or on the wall of a room:

Location is crucial. Identity is rooted in the specifics of place.

The soul of a culture is rooted in soil, and the things that grow from it. And so Wyspianski looked at the plants that grew in the suburbs of Krakow, and drew them.

He painted people – the bonds between people, as much as the individuals themselves.

And, most magnificently, he designed those stained glass windows, to color light and alter the air we breathe when standing in one of those transformed, transcendent spaces that are created.

Walking the streets of Krakow, I sought wonder, and I found it – and something more. A life that I’d not known about, and the expression of that life, in color and image and idea.